This month, the University of Toronto’s Green Chemistry Initiative and the Gainesville ToxSquad teamed up to co-author a post about the Indian Vulture Crisis…

By Shira Joudan (GCI) and Alexis Wormington (ToxSquad)

Pharmaceuticals have drastically changed our society, quality of life, and life expectancy. Advances in chemistry are the driving forces behind the optimization of pharmaceuticals and other synthetic chemicals which have shaped the way we live our lives. Sometimes, a chemical used has undesired side effects, such as non-target toxicity to animals in the environment. A historic example of the consequences of chemical use is the toxicity of the pesticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) to eagles, which was profiled in Rachel Carson’s famous book Silent Spring. Although current regulations require extensive toxicity testing for new chemicals, those with a high production volume can still elicit unforeseen environmental effects on the environment.

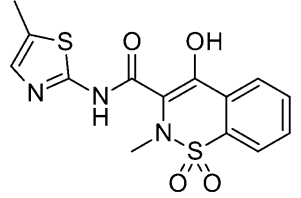

More recently, there have been unforeseen environmental implications of chemical use in another essential bird population in India, a phenomenon now known as the Indian Vulture Crisis. Between 1993 and 2000, Indian vultures (Gyps bengalensis, Figure 1) began to mysteriously disappear, with the population declining by over 97% in less than 10 years (Figure 2).1 Researchers worked frantically to identify the cause, and came up with several theories ranging from infectious disease to food shortage to chemical exposure. Scientists began noticing visceral gout on a majority of the dead vultures,2 which is a sign of kidney failure in birds, and from there it didn’t take long to determine the culprit was a chemical contaminant. In 2004, a paper reported startling amounts of diclofenac (Figure 3) in the tissues of the dead vultures, providing compelling evidence that the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) was the cause of the population collapse.3 To figure out how to restore the vulture population, or at least slow down its decline, researchers needed to figure out how the vultures were being exposed to diclofenac, why it was killing them, and if there was a chemical alternative to the deadly pharmaceutical.

Figure 1. Two G. bengalensis adults with a dead chick.

Figure 2. Catastrophic decline in Gyps vultures in India over a 10-year period. Results from vulture nest monitoring in Koeladeo National Park from 1985 through 2001. [4]

Figure 3. Chemical structure of diclofenac, the pharmaceutical implicated as the cause of the Indian Vulture Crisis.

The problem began when diclofenac was approved for veterinary use in India in the early 1990s, where it was widely utilized to treat inflammation in cattle due to its efficacy and affordable cost. As a result, many livestock carcasses in India were contaminated with diclofenac, which brought catastrophic consequences to any vulture that consumed the carcasses. Vultures within the Gyps genus cannot metabolize diclofenac, and are extremely sensitive to the drug, with toxic doses ranging from just 0.1-0.8 mg/kg depending on the species.1 A vulture would receive a lethal dose of diclofenac after consuming a small amount of contaminated tissue, and die of renal failure within 48 hours. Just one contaminated carcass affected several vultures at once due to their group feeding behaviour, and because of this, diclofenac contamination in as little as 1 of every 200 carcasses would have been enough to cause the decline in the vulture population.5

Although diclofenac is either banned or not used for veterinary purposes in most countries, it is still legally utilized throughout Europe, which has drawn controversy in those countries where it is approved for use in food animals.6

Human-Health Impact of the Vulture Crisis

India is a developing country and relies more on natural processes for the removal of dead animals, where scavengers like vultures play a huge role. With the loss of the vultures, less efficient scavengers such as rats and dogs have moved in to replace them, leading to major problems with disease in the affected areas. Unlike vultures, which are terminal hosts for pathogens due to their strong stomach acid, dogs and rats are reservoirs for diseases – and now these animals are the primary scavengers in India. A rise in feral dogs has caused an increase in the number of rabies cases in humans, which has cost India approximately 998-1095 billion Rupees in healthcare costs between 1992 and 2006 (15-16.5 billion USD).7

In addition to the economic and health costs associated with a rise in infectious diseases, the disappearance of the vultures has also lead to issues with the prolonged decomposition of carcasses. Vultures play a major role in the decomposition process – a group of them can skeletonize a body within a few hours.8 But in their absence, bodies take days or months to decompose, which can lead to issues with water or food contamination. This ‘carcass crisis’ has had cultural implications as well, threatening the ancient Parsi burial tradition where bodies are not buried, but disposed of through natural means (i.e. vultures). Without the vultures, the Parsis struggle to continue the two-thousand-year-long practice9 and are forced to seek alternative methods of body disposal, causing a deep divide within the community.

Diclofenac and Green Chemistry – Could this have been prevented?

The short answer: probably not. For a drug to be approved for human or animal use, toxicity research must be conducted (although these requirements vary by country, read more about how drugs are approved in Canada10 and how drugs are approved in the USA11). Unfortunately, potential ecosystem toxicity (ecotoxicity) is not often at the forefront of the drug-approval process. Even if ecotoxicity studies were performed with diclofenac, it is unlikely that the toxicity to vultures would have been discovered before drug approval, as vultures are not a common test animal used in these types of studies. Only a full chemical assessment with ecosystem modelling and subsequent toxicity tests could have predicted the toxicity to the vultures; but these tests are expensive, time consuming, and not the norm during the current drug-approval process.

In India, farmers cannot afford to lose animals, and rely on affordable NSAIDs such as diclofenac to improve the health and quality of life of their livestock. Since NSAID use cannot be prevented, it is up to green chemists to find a suitable replacement for diclofenac that is efficient, affordable, and less toxic to vultures.

To predict the potential toxicity of a pharmaceutical or chemical to humans and the environment, it is important to consider all interactions that occur once the compound enters the body. Every pharmaceutical has a “therapeutic index” (the difference between an effective and toxic dose), which can vary between different species or susceptible populations (e.g. infants, elderly). If the concentration of a drug exceeds the toxic level, toxic endpoints such as renal failure or death could be observed. The toxic level of a drug depends on two major processes: drug excretion and metabolism. The sum of these two processes determines how quickly a pharmaceutical is broken down and eliminated from the body. In the case of diclofenac, vultures could not metabolize or eliminate the drug, so it was free to wreak havoc on susceptible organ systems. For an NSAID to be a suitable replacement for diclofenac, vultures should be able to break it down and excrete it safely.

Figure 4. Meloxicam, an NSAID alternative to diclofenac.

Currently, meloxicam has replaced diclofenac as an NSAID for livestock in India. Both drugs have a similar mechanism of action in the treatment of inflammation; however, unlike diclofenac, meloxicam is rapidly metabolized and excreted by vultures. In a study where different vulture species were administered meloxicam, researchers observed the production of three metabolites identical to those observed in humans during clinical trials.12 Vultures have the enzymes required for the metabolism of meloxicam (specifically cytochrome P450s and glucuronide transferase). The formation of metabolites alters the biological activity of meloxicam, increasing its water solubility and allowing for faster renal excretion.

Figure 5. Aceclofenac, an NSAID that would not be suitable as a replacement for diclofenac.

Understanding the biological interactions of a drug can also help us eliminate potential replacements for diclofenac. An example of a poor replacement for diclofenac in cattle would be aceclofenac, because it is metabolized to form diclofenac via hydrolysis.13 This particular pharmaceutical would not do anything to improve the vulture population, and should not be selected as a replacement for diclofenac.

Current status and remaining challenges

In 2016, the Indian minister of the environment launched the Gyps Vulture Reintroduction Programme with the hope of restoring the vulture population to 40 million individuals within the next decade through breeding programs.14 Although this effort to restore the Indian vultures is a step in the right direction, there are still many challenges in way of their recovery. Despite the fact that meloxicam is a safer NSAID for use in livestock, diclofenac is still obtained and used illegally among farmers in India due to its affordability. Since the ban of diclofenac for veterinary use in 2006, the decline rate of Gyps has decreased, but vultures are still likely to decline by 18% per year despite the ban.15 Until the drug is completely removed from the equation, the reintroduction and recovery of the vultures remains a challenge.

References

- Swan et al. Biology Letters 2006, 2, 279-282. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2005.0425

- Pain et al. Conservation Biology 2003, 17, 661-671. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01740.x

- Shultz et al. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 271, S458-460. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2004.0223

- Prakash et al. Biological Conservation 2003, 109, 381-390. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(02)00164-7

- Green et al. Journal of Applied Ecology 2004, 41, 793-800. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00954.x

- Becker, R. Nature News 2016 https://www.nature.com/news/cattle-drug-threatens-thousands-of-vultures-1.19839

- Markandya et al. Ecological Economics 2008, 67, 194-204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.04.020

- Reeves, N. Journal of forensic sciences, 2009, 54, 523-528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01020.x

- India’s Parsis search for new funeral arrangements as there are not enough vultures to dispose of bodies. https://www.independent.co.uk/node/6669506

- Government of Canada https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/drug-products/fact-sheets/drugs-reviewed-canada.html

- S. Food & Drug Administration https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/default.htm

- Naidoo et al. Vet. Pharmacol. Therap. 2008, 31, 128-134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2885.2007.00923.x

- Galligan et al. Conservation Biology 2015, 30, 1122-1127. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12711

- Government of India, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=145965

- Cuthbert, et al. PLoS One, 2011, 6, e19069. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019069

Image Credits

Feature image: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0040061