By Hyungjun Cho, member-at-large for the GCI

There is a movement to develop a new type of product life system called ‘the circular economy’ [3]. Part of this movement aims to manufacture products from recycled or raw materials, and after its useful lifetime, re-introduce the product (now considered waste) as recycled material. The motivation for the introduction of the circular economy is to minimize the need for virgin raw material, especially when it originates from non-renewable resources. This effort is being spearheaded by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation with major industry partners like Google, Unilever, Solvay, and Philips, among others [3]. A critical component to the function of the circular economy is developing the capability to turn waste into a desirable product.

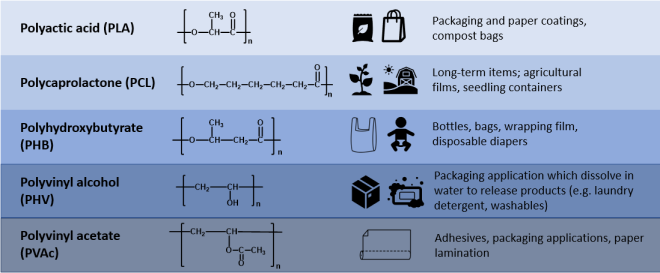

There are several methods of recycling all the different types of materials we use in every day life. This blog will discuss a niche in the ‘plastic to monomer’ field. Evidently, in April of 2019, IUPAC named ‘plastic to monomer’ as part of the 10 chemical innovations that could have high impact in society [6]. Before discussing ‘plastic to monomer’, I must clarify the term ‘plastic’. Generally, plastic is made up of many polymer chains that are physically entangled with one another. A macroscopic analogy is when many electrical wires (think of Christmas tree lights) become entangled: the wires are stuck to each other and the rigidity of the ball of wire is greater than the rigidity of a single wire.

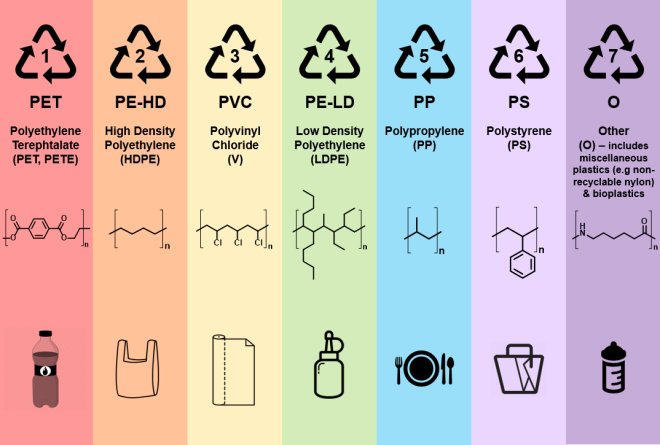

Much like the type of wire influences the tangled ball it forms, the chemical structure of the polymer influences the material properties of the plastic. Examples of properties of plastics include rigidity, elasticity, malleability, gas permeability, friction to skin, transparency, and many others. The polymers that are used for commercial plastic products have been studied and developed for decades to be able perform a specific function. For example, polyvinyl chloride and polystyrene were initially discovered in the 1800s [2,8]. Thus, it would be ideal if the currently used polymers can be de-polymerized back into monomers for recycling purposes. This would be a major move by the plastics industry to become environmentally friendly.

The conventional method to turn polymers into monomer is thermal decomposition. Samples of polymer can be heated to high temperature (typically 220-500 °C) to break some of the bonds that hold the monomers together [10]. When this occurs, radicals can form at the site of the broken bond, which can lead to de-polymerization [10]. The required temperature and how much monomer is formed is dependent on the chemical structure of the monomers that are formed. Thermal decomposition to recover monomer is suitable only for a few types of polymers, such as poly(α-methylstyrene), which has ceiling temperature of 66 °C to propagate depolymerization; the monomer recovery after thermal decomposition of poly(α-methylstyrene) is excellent at 95% [11]. However, for polymers like polyethylene (PE, the most produced polymer) and polypropylene (PP, 2nd most produced polymer), the monomer recovery yield is poor (0.025-2%) [11]. In some cases such as polyvinylchloride (PVC, 3rd most produced polymer), thermal decomposition is even more problematic because PVC will release harmful hydrochloric acid and vinylenes upon heating [11]. Thus, the monomer recovery is poor (1 %) and the process is highly corrosive.

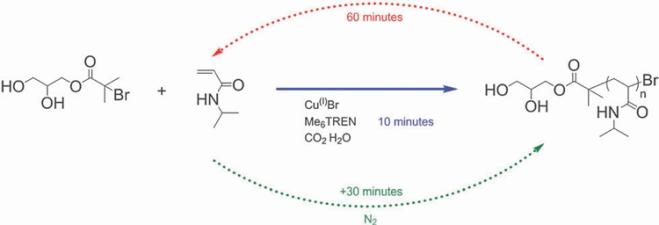

Therefore, one of the key challenges to address for ‘polymer to monomer’ is to perform de-polymerization at a low temperature. There are 4 recent publications that explore this challenge [5,7,9,12]. In general, the authors synthesized polymers using reversible-deactivation radical polymerization (RDRP) techniques and explored the de-polymerization reactions they encountered. Below is a brief highlight from the publications from the Haddleton group [9] and the Gramlich group [5].

Scheme 1: De-polymerization of RAFT polymers with trithioester end-group [5]. Reproduced from ref. [5] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Scheme 2: ATRP of NIPAM in carbonated water, followed by de-polymerization [9]. Reproduced from ref. [9] with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry.

The reports on RDRP followed by de-polymerization highlighted here are not yet ready to make an impact to ‘plastic to monomer’. The authors admit that the mechanism of de-polymerization is unknown. However, these seem to be the first set of reports on de-polymerization occurring at low temperatures. Perhaps these publications could be the birth of the reversible-deactivation radical de-polymerization (RDRDe-P) field. This is especially intriguing because RDRP have already been studied for decades in academia and are being adopted by the polymer industry [4]. Companies like BASF, Solvay, DuPont, L’Oréal, Unilever, 3 M, Arkema, PPG Industries, etc. already claimed patents for technology and products based on RDRP [4]. Somewhat ironically, RDRP was also part of the IUPAC’s 10 chemical innovations for impact on society but not for its potential to recycle polymer [6].

The polymers of the future may not be made from monomers abundantly used today, but the polymers of the future may be degradable through a low energy process.

References

- Alsubaie, F.; Liarou, E.; Nikolaou, V.; Wilson, P.; Haddleton, D. M. Thermoresponsive Viscosity of Polyacrylamide Block Copolymers Synthesised via Aqueous Cu-RDRP. European Polymer Journal 2019, 114, 326–331.

- Baumann, E. Ueber Einige Vinylverbindungen. Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie 1872, 163 (3), 308–322.

- Circular Economy – UK, USA, Europe, Asia & South America – The Ellen MacArthur Foundation https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/ (accessed Jan 5, 2020).

- Destarac, M. Industrial Development of Reversible-Deactivation Radical Polymerization: Is the Induction Period Over? Chem. 2018, 9 (40), 4947–4967.

- Flanders, M. J.; Gramlich, W. M. Reversible-Addition Fragmentation Chain Transfer (RAFT) Mediated Depolymerization of Brush Polymers. Chem. 2018, 9 (17), 2328–2335.

- Gomollón-Bel, F. Ten Chemical Innovations That Will Change Our World: IUPAC Identifies Emerging Technologies in Chemistry with Potential to Make Our Planet More Sustainable. Chemistry International 2019, 41 (2), 12–17.

- Li, L.; Shu, X.; Zhu, J. Low Temperature Depolymerization from a Copper-Based Aqueous Vinyl Polymerization System. Polymer 2012, 53 (22), 5010–5015.

- Liebig, J. Justus Liebig’s Annalen Der Chemie. Annalen der Chemie 1832, 1874-1978.

- Lloyd, D. J.; Nikolaou, V.; Collins, J.; Waldron, C.; Anastasaki, A.; Bassett, S. P.; Howdle, S. M.; Blanazs, A.; Wilson, P.; Kempe, K.; et al. Controlled Aqueous Polymerization of Acrylamides and Acrylates and “in Situ” Depolymerization in the Presence of Dissolved CO2. Commun. 2016, 52 (39), 6533–6536.

- Microwave-Assisted Polymer Synthesis. Springer eBooks 2016

- Moldoveanu, Șerban. Analytical Pyrolysis of Synthetic Organic Polymers; Techniques and instrumentation in analytical chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam ; Oxford, 2005.

- Sano, Y.; Konishi, T.; Sawamoto, M.; Ouchi, M. Controlled Radical Depolymerization of Chlorine-Capped PMMA via Reversible Activation of the Terminal Group by Ruthenium Catalyst. European Polymer Journal 2019, 120, 109181.

- SFPE Handbook of Fire Protection Engineering, 5th ed.; Hurley, M. J., Gottuk, D. T., Jr, J. R. H., Harada, K., Kuligowski, E. D., Puchovsky, M., Torero, J. L., Jr, J. M. W., Wieczorek, C. J., Eds.; Springer-Verlag: New York, 2016.

Scientist: Aleksandra Holownia, Yudin lab

Scientist: Aleksandra Holownia, Yudin lab Scientist: Karl Demmans, Morris lab

Scientist: Karl Demmans, Morris lab Scientist: James LaFortune, Stephan lab

Scientist: James LaFortune, Stephan lab

Scientist: Brian de la Franier, Thompson lab

Scientist: Brian de la Franier, Thompson lab